Traces of Josef Vavroušek in Slovakia

Traces of Josef Vavroušek in Slovakia

The legacy of Josef Vavroušek as an increasingly topical challenge

Mikuláš Huba

Who was and remains to be Josef Vavroušek for us? The answer to this question is, paradoxically, more difficult for those who knew him well than for those who knew him less, or only in some of his areas of activities. He was an extremely multidimensional figure.

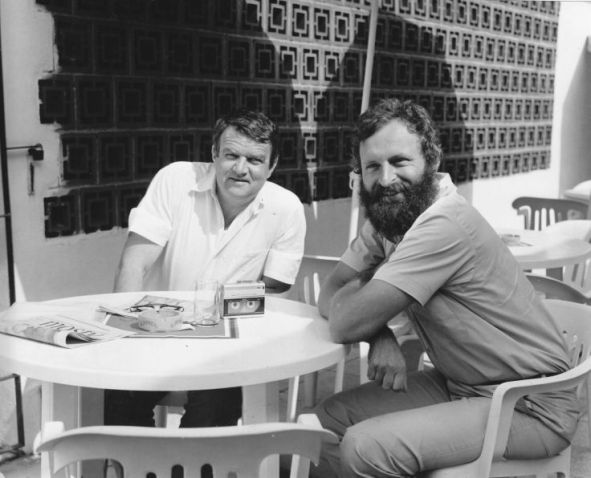

At first he was intrigued by technology, mechanics, and later by system engineering. In parallel, at first emotionally (through climbing and canoeing) and later also rationally: by nature (hence his later interest in ecology and environmentalism). As the youngest participant in the Lambaréné student expedition in 1968, he becomes not only a traveler, but also an expert of the third world, especially its poorest and most troubled part: Africa. Here Vavroušek as a humanist, activist, charitable worker, and philanthropist is born.

After returning home he refuses to sacrifice his convictions to the career and, therefore, lives more or less in seclusion. His personal and professional interest, however, is gaining a new dimension: a social-scientific one. From sociology to public policy. Yet, what is the most important and most unusual, none of the mentioned diverse and seemingly contradictory interests and backgrounds contradict each other in the case of Josef Vavroušek.

Systemic thinking, albeit initially engineering-related, is the key to understanding the functioning of natural as well as social systems and the overall organization of society. However, technical educational background returns him over and over again to the realities of causality, exact numbers and veracious verification of hypotheses. It teaches him not to forget anything essential, including seeming details, because he knows that if anything has been neglected, it will most likely not work. Technical, natural science and social science-oriented education, systemic approach, as well as the permanent search for harmony in the relationship between man and nature, lead him to see beyond the horizon of an isolated phenomenon of society, but also its environment. He feels inherently close to the complexity, synthesis, expression that he will soon discover in the concept of sustainability; he becomes its worldwide protagonist long before he establishes a Society for Sustainable Living in 1992. But even in everyday life he does not like extreme, unilaterally oriented attitudes. He’s not a fundamentalist. He considers PROS and CONS of all realistically imaginable alternatives, variants and development scenarios.

All his previous knowledge, experience and ideals are beginning to awaken in him with new vigor and they integrate in the mid-1980s. He assumes responsibility for the project of forecasting the development of the environment in Czechoslovakia and without hesitation applies a systemic approach to its creation. He is beginning his engagement in the Ecological section of the Biological Society at the then Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. There, he gathers around him a forceful team of independent experts from miscellaneous fields, organizes renowned job seminars and, finally, collectively publishes and distributes in 1988 - in collaboration with Bedřich Moldan and a vast team of co-authors (despite an official ban) - a critical work entitled a Report on the State of Environment in Czechoslovakia.

He travels throughout the country and discusses his prognosis proposal with all the competent ones. New horizons are open to him during several weeks spent at the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). At the time he already intensively cooperates not only with Czech environmentalists around the NIKA magazine, but also with Slovak conservationists from the City Organization of Slovak Association of Conservationists of Nature and Landscape in Bratislava. He also took part in the creation and subsequent defense of their most famous achievement: the appellate publication Bratislava/Aloud that, according to Václav Havel, plays a similar role in Slovakia as Charter 77 in the Czech lands. He enters into fundamental controversies with power: whether about the controversial System of the Danube Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros water works, or in the matter of socially harmful concealment of information on the state and development of the environment. He also uses his foreign contacts: from the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) to the European Parliament.

Since December 8, 1989, when a 150-member representative Forum of conservationists and creators of the environment in Slovakia officially nominated him as deputy chairman of the federal government to be responsible for the environment, he begins to address the issue of how to frame such a central body of public administration. It takes him half a year and requires a vast number of steps, ranging from the amendments to constitutional law, overcoming resistance in the parliament, to gathering the human, operational, budgetary and other capacities needed to build a new “greenfield” institution. Moreover, most of the competent experts who were eligible as professional staff for such a body were just newly employed by the Czech Ministry of the Environment. Still, Vavroušek accomplished this task alongside all of his other activities, and the Federal Committee for the Environment was the center of hectic activities from the very first day until the very last day of its existence, but also an example that the central institution can be useful and effective, but also pro-active, accommodating and even friendly.

It is unbelievable what the Federal Committee under his leadership and in very limited conditions managed to initiate, create, enforce, and support throughout those two years of its existence ... Disputes with adversaries to environmental protection in the government and parliament, controversy with technocrats and economists, new laws, conceptual materials, international conventions, projects, grants, conferences, publications, statements, educational activities, initiatives (such as speaking to the committees of the Hungarian parliament in regards to water works on the Danube), introducing progressive approaches, field work, concrete help to the hundreds of individuals and institutions ...

In the spring of 1990 at the conferences in Dublin and Bergen, Vavroušek co-creates the foundations of systematic pan-European cooperation in the field of the environment and his initiative will assume a concrete form only a year later at Dobříš castle.

Also the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro is approaching and Vavroušek urges not only Czechoslovakia, but also the entire post-communist region of Central and Eastern Europe not to remain in the role of a passive viewer, but to be actively involved in the preparation and course of the summit. In order to pursue this interest, he will undertake a number of initiatives, including organizing a conference of ministers in the region of Tatranská Kotlina, a regional Central European Public forum in Prague, lobbying among colleagues, environment ministers, or two press conferences in Rio itself. But his ambitions reach further and higher. He can see that, despite the nice words, real institutional anchorage and position and support for environmental protection in the United Nations structure are inadequate. He, therefore, proposes a reform of the UN that would change this situation and seeks support for his proposal. But, as is the case of many other timeless initiatives and visions, Czechoslovakia and the world did not yet mature for this necessary change.

When historically the very first evaluation of the state of the European environment was released in 1995, it was written in its introduction that Josef Vavroušek was the spiritus agens of the whole process called Environment for Europe. The mentioned report has a poignant subtitle - Dobříš Assessment. This is because the whole Environment for Europe process began to be written in June 1991 at Dobříš castle in former Czechoslovakia. This is where the first pan-European conference of environment ministers took place. Josef Vavroušek was its initiator and main organizer. At the conference he tried to push through his view of our continent, which he perceived as a unified, very fragile ecosystem, suffering from many environmental problems, which require intensive and well-coordinated care, both at national and international levels. But not only that. Europe-wide efforts to improve the environment on our continent were considered in Dobříš to be the most promising platform for the desired integration of Eastern and Western Europe, divided by the Iron Curtain for four decades. It was meant to be integration based on a joint transition to a trajectory of sustainability. Never before, and unfortunately not even after - despite all the integration campaigns and rituals - this vision seemed to be as real as it was in the times of Dobříš.

This may be evidenced by the conclusions of the Dobříš conference, which were very promising. Ministers, among other things, committed themselves to do the following:

a/ improve the European information and monitoring system of the environment and rapidly establish the European agency for the environment as an institution of the European Community (today’s EU – author’s note), which would also be open to non-European community members;

b/ coordinate European legislation, programs and policy in the area of the environment, including regional programs, programs for major river basin, and also environmentally friendly transport systems;

c/ continue discussions on fundamental changes in the hierarchy of human values and behavioral patterns;

d/ improve the functioning of existing international organizations aimed at the environment and integrate the environmental dimension into the UN system;

e/ enhance nature protection in Europe;

f/ publish a report by the end of the year 1993 on “The state of the environment in Europe” and update it at regular intervals;

g/ hold a similar pan-European conference of the ministers of environment in the Swiss Confederation.

Which ones of these intentions have been accomplished? Quite a lot, though not in their ideal form. Let’s address them one by one.

The first commitment was accomplished in the form of the creation of a European Environment Agency based in Copenhagen, which has a truly pan-European scope. New monitoring mechanisms have been introduced, among others CORINE Land Cover system, which is used to evaluate the state and changes in land use and land cover.

There has also been some progress in the area of the second commitment. This clearly concerns the enlarged EU, which now has twice as many members as at the time of the Dobříš conference, but in its mediated form also other European countries, signatories of the European conventions or conventions of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).

There has been little progress in the functioning of international environment-oriented institutions since the times of Dobříš. The UN has not yet been reformed in line with Josef Vavroušek’s ideas, although a similar initiative from the European Union did occur at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Ultimately, however, it didn’t work out due to the resistance on the part of the United States. What more or less does work is the already mentioned process Environment for Europe in UNECE.

The fifth commitment from Dobříš speaks about enhancing the protection of European nature. Here the results are ambiguous: rather more negative than positive. Europe’s nature continues to deteriorate and, especially to the east of the former Iron Curtain, it faces new challenges and threats. For example, by the automobile boom, not always well conceived construction of highways and water works, mining of raw materials, unregulated construction or commercial tourism. In the institutional sphere, the often debated program for the protection of European natural values of extraordinary (pan-European) importance: Natura 2000 should be of benefit in this regard.

The commitment no. 6 is clearly being followed in the form of the above mentioned Dobříš assessments, which present a unique report rich in data, facts and evaluations on the state of the environment in Europe.

Commitment no. 7: since the times of Dobříš, the conference has been held not only in Lucerne, Switzerland, but also in six other cities: in Sofia in Bulgaria, Aarhus in Denmark, Kiev in Ukraine, Belgrade in Serbia, Astana in Kazakhstan and Batumi in Georgia. Each of them had its strengths and weaknesses, but they all contributed with something new, something that would give new contours and rules to Europe’s system of environmental protection.

As you may have noticed, we have omitted to mention the fulfillment of commitment no. 3 concerning the values for a sustainable future. None of the aforementioned points of the program mattered to Josef Vavroušek as much as this one. While there is much talk about the values in expanding Europe, compromises, superficial attitudes and pragmatic interests are increasingly winning. And this is the case of the third commitment from Dobříš and its place on the European environmental agenda. Already at the first conference following Dobříš, which was held in Lucerne, this dimension was missing in the focus of the ministerial program. Among other things, Vavroušek wrote in the Lucerne Memorandum, in which European protectionists made appeals to the ministers, the following:

“The root cause of all the sources of global environmental problems is one key factor: specifically human values that permeate and determine our Euro-American or “North” culture.

Selfishness, hedonism, and greed are the main driving forces of “northern” economies, but at the same time they are poisons that tarnish relations among people as well as between human society and nature.

On the one hand, to avoid the dangers stemming from further air and water pollution, social explosions, anarchy, chain bankruptcies, violence and crime, as well as from enormous migration waves from the East and South to the West and North and, on the other hand, to avert the dangers associated with continuing the egoistic and wasteful Western way of life can only be achieved through pan-European cooperation, based on our sense of solidarity and natural responsibility.

We must find a balance between human rights and freedom on the one hand and human responsibility for other beings and the whole planet Earth on the other hand, between individualism and collectivism, between self-gratification and respect for nature ...

The tasks we are talking about are probably the most important tasks of our time ... “

It was great and few could disagree with it. And yet ... It was at that time understood more by environmental America than by Europe: Mr. and Mrs. Meadows, Amory Lovins, Hasel Henderson, Susan Murcott, the so-called Balaton Group ...

How he would perceive and evaluate our accession to the EU, the development of environmental policy and diplomacy, or the current cynicism of the top officials (not only) of our two states in relation to the refugees, can only be considered at the hypothetical level.

In view of his warnings about the emergence of a new Europe-dividing curtain, this time not the iron one, but electronic or information-related, and since he always claimed that the environment knows no borders, I think Vavroušek would probably welcome the enlargement of the EU by the countries of Central-Eastern Europe, though (probably) not quite free of worries.

In addition, although he was a thinker drawing on European spiritual principles of humanism, he surpassed this traditional European dimension of thinking in at least two directions: towards the third world and globalism and towards the things beyond man himself, that is, towards “extra-human” nature.

In conclusion, we have been left with so much after Josef’s death. And it concerns not only the things that are tangible or those that remain on paper, or affect our lives in the form of laws. It also includes the level of visions, ideals, inspirations, honest attempts and unfulfilled intentions. Last but not least, it also includes what is increasingly rare in today’s relativized world. To this day, Josef Vavroušek represents for us a positive human model of charismatic personality of extraordinary talent, knowledge, vision, scope and pragmatism, ability, strength, tenacity, character, integrity, openness, empathy and solidarity.

Mikuláš Huba

Researcher at the Institute of Geography of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, honorary chairman of the Society for Sustainable Living in the Slovak Republic, founding member of the Slovak Protection Council and member of the committee of Josef Vavroušek Award at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University.